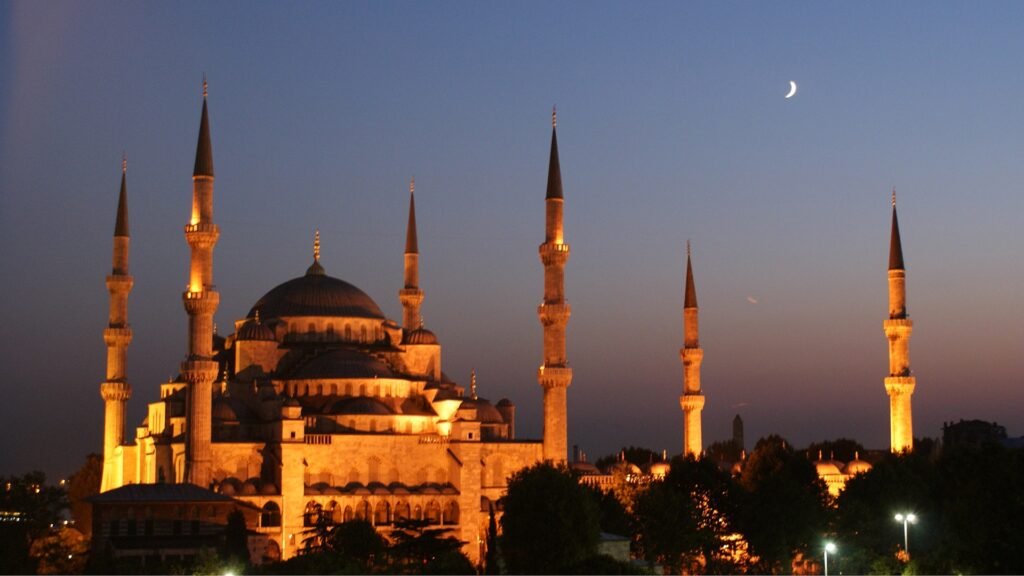

Imagine treading through the helical streets of medieval Baghdad, passing by markets, and fussing with merchants selling exotic goods from remote lands. Amidst the clamor, you hear snippets of conversation about the latest scientific discoveries: a new theorem in mathematics, a groundbreaking technique in medicine, or a revolutionary invention in astronomy.

Yet today, that light has darkened. The once-thriving centers of science and learning have fallen into the wreckage, and the spirit of curiosity and discovery has shrunk away. What happened to the Muslim world’s appetite for knowledge? How did we lose our pattern, and how can we find our footpath heretofore?

After conducting my investigation, I have concluded that various factors have contributed to the decline of Islamic science. Among these is the political instability that plagued the Muslim world in the aftermath of the 13th century, the absence of organized associations of scientists, the erosion of rational attitudes, the impact of colonization, and a dearth of financial resources for research projects on a global scale.

The vicissitudes of politics, set in motion by the collision of civilizations at Khilafat in the 13th century, had a profound impact on the realm of science in the Muslim world. As recorded in the annals of science, during the golden age of Islam, scientific pursuits were held in high esteem by the state, with the Khalifa assuming the mantle of authority and convening the most illustrious philosophers, intellectuals, and thinkers of the time to partake in erudite discussions and to provide generous support to scientific endeavors. The House of Wisdom in Baghdad, an iconic symbol of scientific progress, was one such ambitious venture launched during this period of scientific enlightenment. However, as the ebb and flow of cultural and political fortunes took hold, these once-cherished bastions of scientific advancement were eventually forced to shutter their doors, much to the detriment of scientific exploration and innovation. (See: The Cash of Civilization by Samuel P. Huntington)

The siege of Baghdad in the year 1200 marked a watershed moment in the history of science, which had flourished in the Muslim world. As the forces of Halooka Khan, the Mongol commander, overran the learned city, the illustrious Khalifa Mutaseem was apprehended and cast into a dungeon, where he met his tragic end in the grip of starvation. The Caspian report attests to the ghastly fact that: a million books, documents, and parchments were set ablaze by the marauding hordes. The river waters, tainted with the black ink of the torched tomes, ran dark for a week, a somber reminder of the incursion that led to the downfall of science’s shining gem in Muslim lands. (Reference: Islam and Science: Caspian Report, Youtube)

If we were to recollect the mighty influence of al-Ma’mūn, that illustrious caliph who transformed the House of Wisdom from a mere palace library into one of the greatest centers of learning known to man, we would truly comprehend the pivotal role played by a patron of scholarship. According to Book Pathfinders, “we must recognize the significance of an era of peace and prosperity, for it was such a time that fostered an environment ripe for the gathering of brilliant minds, imbued with infectious enthusiasm, unwavering passion, and ceaseless drive.” (Source: Pathfinders; the golden age of Arabic Science)

Even in the thriving metropolis of ninth-century Baghdad, we observe that subsequent caliphs, possessing a weaker inclination towards the fostering and financing of scientific scholarship, inevitably experienced a decline in the rate of scientific advances. Alas, such is the way of things when the powers that be are bereft of the wisdom and foresight necessary to nurture the minds that drive human progress.

“The history of science, like the history of all civilization, has gone through cycles.”

(Abdus Salam, Nobel Laureate)

It has been suggested by certain observers that the decline of science in the Muslim world cannot be attributed solely to the siege of Baghdad, but rather to an irrational attitude that impeded scientific progress. As elucidated by George Saliba, an esteemed American Professor of Arabic Science, in his work entitled Islamic Science and the Renaissance of Europe, Muslims may have placed the entire burden of responsibility on Halooka Khan for the decline of science, but in actuality, it was a lack of a scientific mindset that led to the demise of scientific pursuits.

The contention has been put forth in the Western world that the conflict between the Islamic orthodoxy and the rationalist Mu’tazilite movement, culminating in the work of the theologian al-Ghazāli (1058-1111), served as a harbinger of the decline of the scientific age in the region. The Incoherence of the Philosophers, a treatise by al-Ghazāli, featured a critique of the philosophy of Ibn Sīna and other intellectuals. These individuals’ fascination with Aristotle and their assimilation of his ideas into their philosophy came under attack in al-Ghazāli’s work. Consequently, al-Ghazāli’s ideas represent a definitive shift towards a more conservative, and perhaps even mystical, interpretation of Islamic theology.

In contemplating the legacy of Al-Ghazāli, it cannot be denied that he remains one of the most respected and influential thinkers in Islamic history. His ideas have reverberated through the ages and left an indelible imprint on mainstream Islamic thought. It is not an exaggeration to say that his influence extended beyond the Islamic world and even found its way to Europe, where he influenced the likes of Thomas Aquinas.

However, we must also acknowledge that the establishment of the school of thought that grew around his work, the House of Wisdom, had a profound impact on the trajectory of Islamic philosophy. It marked a turning point away from rationalism and toward a more inward-looking, spiritual approach. This shift had a lasting impact, leading many to label the great thinkers who came before Al-Ghazāli as heretics and undermining the rich contributions they made to the world of ideas.

It would be remiss to view Al-Ghazāli solely through the lens of this controversy. He was himself a highly competent scientist and thinker, and his ideas continue to hold relevance and resonance today. Yet, we must also grapple with the fact that his legacy has been a complex one, with both positive and negative implications for the development of Islamic philosophy and thought.

It is quite absurd to continue to uphold Al-Ghazāli’s critique as the primary cause for the decline of rational scientific inquiry. Al-Ghazāli’s attack was directed towards a particular theological and metaphysical perspective that relied on Platonic and Aristotelian logic, which he believed was contrary to Islamic teachings. This philosophical disagreement has unfortunately been oversimplified into a battle between irrational religion and rational science, which is a rather foolish notion. Moreover, it is important to note that other fields of study such as mathematics, astronomy, and medicine were not significantly affected by this dispute, as they were not based on purely philosophical foundations. To continue to attribute the decline of scientific inquiry to this particular incident is like blaming the sun for setting at the end of the day; it is both nonsensical and unproductive. (Reference: The House of Wisdom by Jim Al Khalili)

The colonization of Asia and Africa by Western powers has played a significant role in this decline. These colonizers, driven by their insatiable greed for wealth and power, not only plundered the resources of their subjugated subjects but also dismantled the very foundations of the enlightenment that had flourished in these lands for centuries. The great American historian and philosopher, Will Durant, bore witness to the brutalities of British rule in India during his visit to the country in 1930. In his magnum opus, “A Case for India,” Durant vividly describes how the British conquest of India marked the ruthless obliteration of a highly civilized society by the infamous East India Company. Unrestrained by any sense of morality or ethics, the East India Company plundered and pillaged its way through a temporarily helpless and disordered nation, resorting to bribery, murder, annexation, and robbery as its preferred means of achieving its nefarious goals. This ignoble legacy of unsportsmanlike and illegal plunder continues to haunt these lands even today, almost a century later. (Reference Book: An Era of Darkness by Sashi Tharoor)

Significant declarations have been proclaimed, urging the minds of the Muslim World to unite and enhance their science culture. One may delve into a research report entitled “Science at the Universities of the Muslim World,” with a foreword by Tan Sri Zakri Abdul Hamid, Science Advisor to the Prime Minister of Malaysia, for further insight. This report implores us to consider implementing changes such as restructuring curricula, constructing new institutions, and forming scholars’ associations.

What is the path that lies ahead? How can we once again attain the scientific prowess that once shone in the Muslim world? And what manner of measures may be adopted in this lamentable climate? Verily, it is not within the realms of possibility to further expound upon this discourse, yet the direction ahead shall be deliberated upon in a forum yet to come.

One thought on “Decline of Science in the Muslim World”

I really like your article and the effort you put in.This is very useful as you’ve specifically explained some of the main reasons regarding decline of science in the Muslim World, found following statement highly worthy,

“we must recognize the significance of an era of peace and prosperity, for it was such a time that fostered an environment ripe for the gathering of brilliant minds, imbued with infectious enthusiasm, unwavering passion, and ceaseless drive.”

Following the above, could be helpful for finding our path ahead!