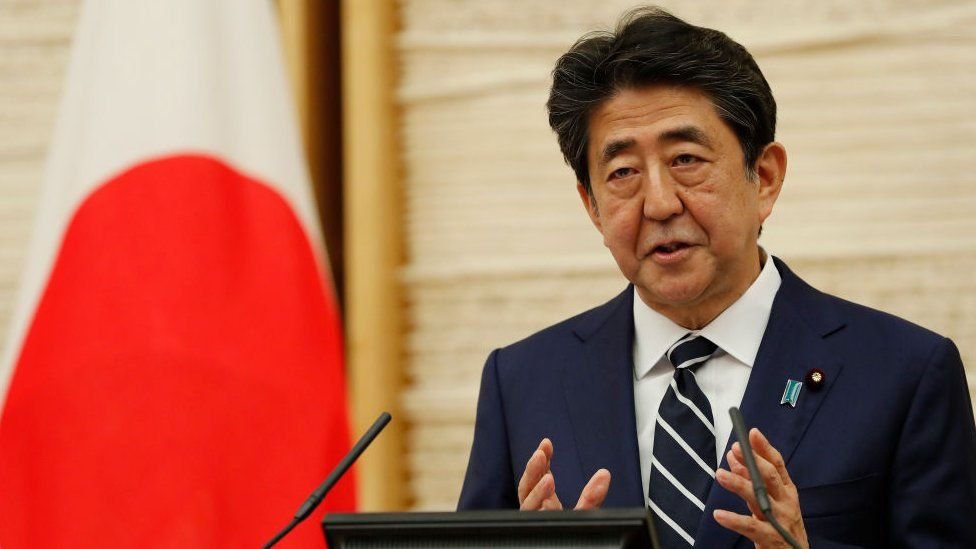

Why Japan is angry about a state funeral for Shinzo Abe

The world’s “great and good” gathered in London a week ago for the state funeral of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II. Many of them are now on their way to the other side of the world for another state funeral: that of Japan’s assassinated former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

However, the Japanese appear to be unimpressed, not least because it is expected to cost $11.4 million (1.65 billion yen; £10.1 million).

Opposition to the state funeral has grown in recent weeks. According to polls, more than half of the country’s population is now opposed to keeping it.

A man set himself on fire near the prime minister’s office in Tokyo earlier this week. On Monday, around 10,000 people marched through the streets of the capital, demanding that the funeral be postponed.

On the other hand, the event is attracting Japan’s allies from around the world. US Vice President Kamala Harris will attend in place of US President Joe Biden. Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong will be present.

So is Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, as are three of his predecessors. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi will fly to Tokyo to pay his respects to Abe instead of attending the Queen’s funeral.

What does it say about Abe if, even as world leaders gather for his funeral, many in his own country oppose it?

Why Japan is angry about a state funeral for Shinzo Abe

To begin with, this is not a typical occurrence. State funerals are only held for members of the Imperial Family in Japan. Only once since World War II has a politician been given this honor, and that was in 1967. So the fact that Abe will be given a state funeral is significant.

It’s partly because of how he died – he was shot at an election rally in July. And Japan wept for him. According to polls, he was never particularly popular, but few would argue that he brought the country stability and security.

As a result, the decision to hold a state funeral for him reflects his stature. No one has served as Prime Minister for longer, and no other postwar politician has had such an impact on Japan’s global standing.

“He was ahead of his time,” says political scientist and former Abe advisor Professor Kazuto Suzuki.

“He recognized the shifting balance of power. Of course, a rising China will distort the balance of power and reshape the regional order. As a result, he desired to assume command.”

Professor Suzuki cites the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), President Barack Obama’s grand plan to unite all of America’s Asian Pacific allies in a massive free trade zone.

When Donald Trump pulled the US out of the TPP in 2016, everyone expected it to fail. But it didn’t work.

Abe took over as Prime Minister and drafted the even more ambiguous Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, or CPTPP.

It’s a terrible name, but it signaled Japan’s renewed willingness to lead Asia. He was also instrumental in the formation of Quad, an alliance of the United States, Japan, India, and Australia.

The changes Abe made to Japan’s military are even more significant.

In 2014, Japan’s then-prime minister pushed legislation that “reinterpreted” the country’s pacifist postwar constitution.

It enabled Japan to engage in “collective self-defense.” For the first time since World War II, Japan can join its ally in military action beyond its own borders.

The legislation was highly contentious, and the repercussions can still be felt today. Thousands of people marched in Tokyo against the state funeral, accusing Abe of leading Japan to war.

“Abe signed the bill for collective self-defense,” protestor Machiko Takumi said. “It means Japan will fight alongside the Americans, which means he enabled Japan to go to war again, which is why I am opposed to a state funeral.”

Japan has been traumatized by war. People are angry about Abe for reasons other than their memories of atomic bombs.

Japan’s postwar constitution states unequivocally that the country “renounces the right to wage war.” Abe should have called a referendum if he wanted to change that. But he knew he was going to lose. Rather, his legislation “reinterpreted” the meaning of the constitution.

“Abe is seen as someone who was not accountable to the people,” says Sophia University Professor Koichi Nakano. “Whatever he did was against constitutional principles. He went against democratic principles.”

To his supporters, however, all of this is beside the point. Before any other world leader, Abe recognized China’s growing threat and determined that Japan needed to become a fully paid-up member of the US-Japan alliance.

“Abe had a very futuristic vision,” says Mr. Suzuki, his former advisor. “He predicted that China would rise while the US would withdraw from the region. He realized that in order to keep the United States involved in this region, we needed to be able to defend ourselves.”

A rearmed and capable Japan is certainly welcomed by Washington, as are many other Asian countries concerned about China.

In Canberra and Delhi, Abe found willing partners. Mr. Modi declared a national day of mourning in India after his death.

But there is one place where Abe is not being remembered: Japan, where he was repeatedly denounced as a warmonger and revisionist.

China is the location. It could explain why Beijing sent Vice President Wang Qishan to London but is sending a former science and technology minister to Tokyo who no one outside of China has ever heard of.